Korea S Nuclear Program 2007 Elantra

Update North Korea claimed to have tested a hydrogen bomb on September 3, its sixth nuclear test and approximately six times as strong as its test in September 2016, according to the South Korea’s meteorological administration. This followed weeks of rising tensions and a war of words between U.S. President Donald Trump and the pariah state about nuclear capability.

The spark for the (so-far) verbal fire was Pyongyang’s fresh claim in early August that it is able to hit the U.S. Pacific island of Guam with a nuclear strike. North Korea aspires to have the entire U.S. Mainland within striking range. Here is what we knew about the bite of the North’s nuclear bark prior to the latest test. How Powerful Is a North Korean Warhead? Tests involving nuclear explosions show progress regarding the power of the blast North Korea can cause.

Of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Surrounding North Korea’s nuclear program and the six. People's Republic of Korea. Rihanna Album Torrent Download. Last modified 2007.

A 2006 explosion detonated a plutonium-fueled atomic bomb with a yield equivalent to 2 kilotons of TNT, data from D.C.-based think tank the shows. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima by the U.S. Military in 1945 had an estimated yield of about 16 kilotons. North Korea’s latest tests have since surpassed that figure more than twofold. In 2009, a test increased this power four times from the 2006 blast to 8 kilotons; several tests later, a September 2016 blast yielded 35 kilotons. The ability to deliver this blast to the U.S. Is the challenge North Korea faces now.

Tests of their missiles’ range have shown a considerable increase of capabilities, stretching now to potentially 10,400 kilometers (6,500 miles). These test launches have not been carried out with a nuclear warhead, and the calculations of putting the two together is what keeps North Korea from boasting the ability to fire a warhead at massive distances. Targeting the U.S. Mainland requires precisely this sort of capability. The Warhead Takes Flight Warhead miniaturization is a crucial step in turning a potential nuclear bomb into a nuclear missile. The process of miniaturization consists of finding the most compact design to mount the physics package—the nuclear payload of a missile—on the ICBM without disruting the missile's flight.

The way North Korea is likely pursuing this is by using the common so-called “implosion design,” in which the nuclear fissile material is exploded by a chamber of conventional explosives, Matthew Kroenig, nonproliferation expert at the Atlantic Council, says. “You have your fissile material—plutonium is preferred—in a loosely packed sphere, and you surround it with conventional explosives. You need them to detonate at the same time; otherwise the plutonium blows out the other end.” If the detonations are not simultaneous, the best-case scenario is the triggering of a chain reaction that mostly wastes the fissile material. The worst-case scenario is that it does not cause a nuclear chain reaction at all.

This is the design North Korea is probably already using, says Tom Plant, director of the proliferation and nuclear policy program at London’s Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). “Having an implosion design that does it on the ground is quite different than having one that does it in the air, but again, this is not something North Korea is incapable of addressing.” The Warhead Must Survive Space and Re-entry Despite a report on August 8 by the that “North Korea has successfully produced a miniaturized nuclear warhead that can fit inside its missiles,” whether the warhead can survive the ICBM flight is another matter. The distinction can be crucial, Plant says. “In relation to that particular U.S. Intelligence assessment, the language is always worth paying very close attention to.

The assessment states that North Korea has produced nuclear weapons for ballistic missile delivery, to include delivery by ICBM,” he says. “That’s subtly different from saying that those weapons fit in a survivable re-entry vehicle. “In casual conversation, it may be natural to make the inference between the two,” he continues. “In an intelligence assessment, it needs to be absolutely explicit.” Put simply, the warheads may be designed with the intention of taking off inside an ICBM. The full journey of such a missile would traverse extreme cold and scalding heat upon re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere; that is the biggest test for the segment of the missile to ensure the full nuclear punch is delivered on target. If the re-entry vehicle fails to deliver the fissile material through the atmosphere, the strike is a botch. Beyond the fissile material, the re-entry vehicle would likely have additional engineering features such as heat shields, an ablative shield, potentially the fusing system, Plant says.

All must be accounted for in the weight equation. Would a Bigger Rocket Help?

Currently, North Korea’s prospective intercontinental harbinger of nuclear doom is the Hwasong-14 missile. Video from Japanese last month shows it disintegrating as it re-enters the atmosphere. That could be a show of the re-entry vehicle’s problems, says Karl Dewey, CBRN analyst at Jane’s by IHS Markit, or the result of a lopsided trajectory during the launch. Other problems may have caused missile ignition, such as a deliberate self-destruction to prevent foreign salvage. If the Hwasong-14 is flawed, North Korea could theoretically opt to make a bigger missile capable of carrying more cargo.

“Easier said than done, however, especially when one considers operational requirements such as deployability,” Dewey says. “For example, the Unha/Taepodong is often considered to be for weapons, but the considerable preparation time makes this unlikely.” The missile in question, reported as a possible, has proven physically unsuitable for the job.

North Korea expert John Schilling at the concluded in 2015 that it is “too large and cumbersome” for warhead delivery. The Hwasong-14 remains Pyongyang’s main option at present. Would Russia and China Step In? Any foreign help could speed up North Korea’s ICBM nuclear program.

In the past, the Soviet Union and China aided Pyongyang’s nuclear energy and missile programs. Moscow assisted North Korea from the late 1950s to the 1980s, helping build a nuclear research reactor and design missiles, and providing light-water reactors and some nuclear fuel. China joined forces with North Korea in developing and producing ballistic missiles in the 1970s. Pakistan also has been crucial to North Korea’s nuclear program, to produce weapons-grade uranium. During the Cold War, however, Moscow and Beijing remained wary of sharing militarized nuclear technology with Pyongyang.

Both are currently committed to nonproliferation. “China and Russia have a strong interest in nonproliferation,” Plant says.

“I can see a ballistic missile connection from North Korea to Iran, more so than the other way around.” Even that sort of partnership is unsubstantiated in evidence, Plant notes, as the uranium enrichment technology both countries use is different. “What I would be worried about is North Korea acting more as a supplier than a recipient,” he says, recalling suspicions 10 years ago that Pyongyang was cooperating with the regime in Syria. In 2007, Israeli air force jets bombed what in the making, modeled on North Korean designs. This article was updated to include early reports that North Korea had tested another nuclear weapon in early September.

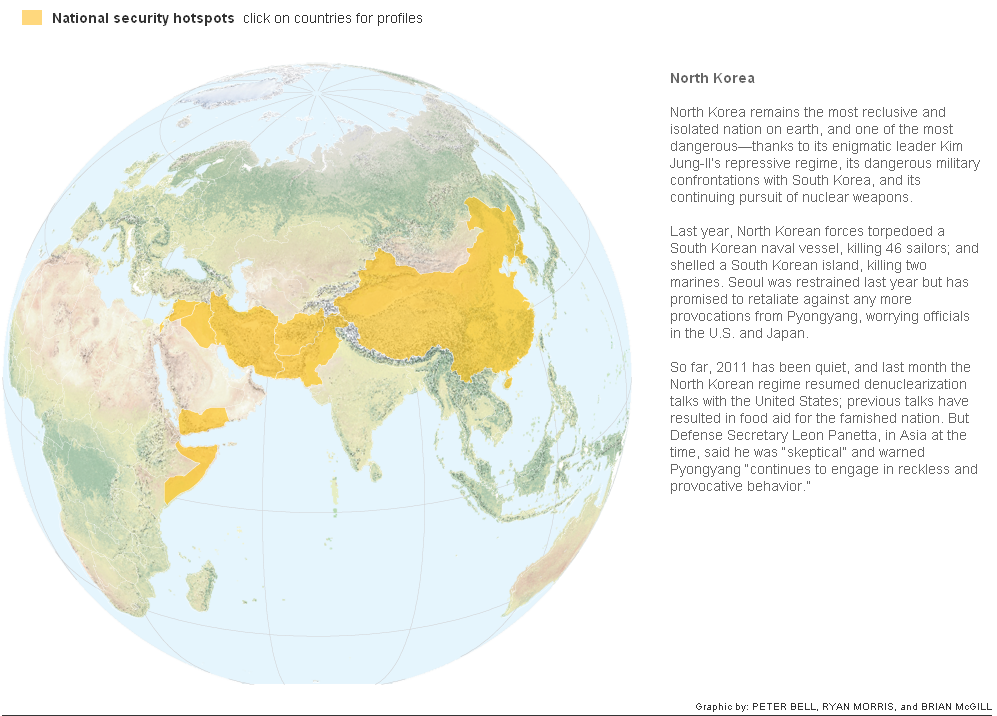

North Korea (formally, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea or DPRK), has active and increasingly sophisticated and ballistic missile programs, and believed to possess chemical and biological weapons capabilities. North Korea unilaterally withdrew from the in January 2003, is not a party to the, and has conducted six increasingly sophisticated nuclear tests since 2006. The DPRK is not a party to the, and is believed to possess a large chemical weapons program.

Despite being a state party to the and evidence suggests North Korea may maintain an offensive biological weapons program. Download Mapinstall Software Pc Free. In defiance of the international community, which has imposed heavy on North Korea for its illicit behavior, the country has continued to escalate its activities. In July 2017, North Korea successfully tested its first, and in September 2017 it conducted a test of what it claimed was a. [1] *Graphic shows DPRK capabilities as of November 2017 Click to Nuclear North Korea’s nuclear ambitions date to the Korean War in the 1950s, but came to the attention of the international community in 1992, when the discovered that its nuclear activities were more extensive than declared. [2] The revelations led North Korea to withdraw from the IAEA in 1994.

In an effort to prevent North Korean withdrawal from the NPT, the and North Korea negotiated the, in which Pyongyang agreed to freeze its nuclear activities and give access to IAEA inspectors in exchange for U.S.-supplied and energy assistance. [3] The Agreed Framework broke down in 2002. [4] North Korea unilaterally withdrew from the NPT in January 2003, prompting,,,, and the United States to engage North Korea in the Six-Party Talks in a further attempt at a diplomatic solution to the country’s nuclear program. The talks fell apart in 2009, and no serious diplomatic initiatives to denuclearize North Korea have occurred since. [5] North Korea produces both and, with one U.S.

Government estimate in 2017 suggesting the country may be producing enough nuclear material each year for 12 additional nuclear weapons. [6] Biological North Korea signed the Geneva Protocol and acceded to the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) in 1987.

Intelligence sources consider North Korea capable of biological weapons production and weaponization. [7] [8] However, open source information on the status of the DPRK's biological weapons program varies. The 2016 Defense White Paper by South Korea's Ministry of National Defense estimates that the DPRK possesses the causative agents of and smallpox, among others.

Secretary of Defense’s 2015 report assesses that North Korea may consider the use of biological weapons as an option, contrary to its obligations under the Biological and Toxins Weapons Convention (BTWC), but does not reference specific agent stockpiles. [10] Chemical North Korea is not a signatory to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).

[11] The DPRK’s pursuit of chemical weapons dates to 1954, and it most likely obtained indigenous offensive CW production capabilities in the early 1980s. [12] A South Korean 2016 Defense White Paper estimates that North Korea has stockpiled between 2,500 and 5,000 tons of CW agent. [13] Pyongyang has concentrated on acquiring,,, and. Reports indicate that the DPRK has approximately 12 facilities where raw chemicals, precursors, and agents are produced and/or stored, as well as six major storage depots for chemical weapons. [14] The United Nations Human Rights Council reported that North Korea may have tested chemical weapons on prisoners and the disabled in February 2014, though it could not independently confirm the accuracy of defector accounts. [15] In February 2017, the half-brother of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, Kim Jong-nam, was assassinated in the Kuala Lumpur international airport.

Following the attack, Malaysian officials announced that Kim Jong-nam was killed by suspected North Korean agents wielding the nerve agent. [16] Missile North Korea possesses a large and increasingly sophisticated program, and conducts frequent missile test launches, heightening East Asian tensions. In 2017, North Korea successfully tested the Hwasong-14 and Hwasong-15, its first ICBMs, which experts believe are capable of delivering a nuclear payload anywhere in the United States. North Korea’s initiated its ballistic missile program in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when it acquired Soviet -type missiles from and reverse-engineered them.

[17] In the early 1990’s, with assistance from and several other countries, North Korea began producing Nodong medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBM). [18] North Korea has developed and tested a number of new missiles since Kim Jong-un’s ascension to leadership in 2011, such as the Intermediate-Range Hwasong-12 and the Pukguksong solid fuel missiles.

[19] In addition to its land-based ballistic missiles, North Korea has successfully tested a, the Pukguksong-1. [20] North Korea also has a, the Unha, which uses technologies closely related to its ballistic missiles. [21] North Korea is not a member of the. Visit the CNS/NTI for a comprehensive visualization of all of North Korea’s missile tests since 1984. Visit the to interact with 3D models of North Korea’s missiles.

Sources: [1] Gabriel Dominguez and Karl Dewey and Markus Schiller and Neil Gibson, “North Korea claims second ICBM test launch shows all of US is within range,” IHS Jane’s Defence Weekly, 21 July 2107, www.janes.com. “Large nuclear test in North Korea on 3 September 2017,” Norwegian Seismic Array, 3 September 2017, www.norsar.no.

[2] “Application of Safeguards in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” IAEA, 2 September 2011, www.iaea.org. [3] “The DPRK’s Violation of its NPT Safeguards Agreement with the IAEA,” IAEA, www.iaea.org.

[4] “CIA estimates on North Korea’s nuclear program provided to Congress on November 19, 2002,” Federation of American Scientists, www.fas.org. [5] Nick Hansen and Jeffrey Lewis, 'North Korea Restarting its 5 MW Reactor,' 38 North, 11 September 2013, www.38north.org. [6] Ankit Panda, “North Korea May Already Be Annually Accruing Enough Fissile Material for 12 Nuclear Weapons,” The Diplomat, 9 August 2017, www.thediplomat.com. [7] “Unclassified Report to Congress on the Acquisition of Technology Relating to Weapons of Mass Destruction and Advanced Conventional Weapons, Covering 1 January to 31 December 2011,” Federation of American Scientists, www.fas.org. [8] 'North Korea's Chemical and Biological Weapons Programs,' International Crisis Group, 18 June 2009, www.crisisgroup.org. [9] Republic of Korea, Ministry of National Defense, '2012 Defense White Paper,' 11 December 2012, p.

36, www.mnd.go.kr. [10] Office of the Secretary of Defense, 'Military and Security Developments Involving the Democratic People's Republic of Korea 2015,' www.defense.gov. [11] Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, 'Non-Member States,' www.opcw.org.

[12] Joseph Bermudez Jr., 'North Korea's Chemical Warfare Capabilities,' 38 North, 11 October 2013, [13] 'Strategic Weapon System, Korea, North,' Jane's Sentinel Security Assessment, 5 July 2010. [14] 'Strategic Weapon System, Korea, North,' Jane's Sentinel Security Assessment, 5 July 2010. [15] UN Human Rights Council, 'Report of the Detailed Finds of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea,' A/HRC/25/CRP.1, p. 93, 7 February 2014, www.un.org. [16] “Malaysian Police Say Kim Jong Nam Killed with VX Nerve Agent,” James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, 24 February 2017, Nonproliferation.org.

[17] Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “Occasional Paper No.2: A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK,” James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, 1999, www.nonproliferation.org. [18] “No Dong 1,” Center for Strategic and International Studies Missile Defense Project, www.missilethreat.csis.org.

[19] “The CNS North Korea Missile Database,” Nuclear Threat Initiative, www.nti.org. [20] Ju-min Park and Jack Kim, “North Korea fires submarine-launched ballistic missile towards Japan,” Reuters, 23 August 2016, www.reuters.com. [21] “The CNS North Korea Missile Database,” Nuclear Threat Initiative, www.nti.org.